You can use the database’s thesaurus to find subject terms. Different databases may use different subject headings, so it is a good idea to check what terms the database actually uses. MEDLINE uses MeSH (Medical Subject Headings), which is what the OCOM Library also uses to organize materials.

CLICK HERE to see the boolean search terms for finding specific types of research (i.e., Systematic Review, Randomized Controlled Trial) in PubMed.

A word to the wise: Even filters have their limits. When you search multiple databases at once in EBSCO, each of those databases has their own set of individualized filters. The problem with searching in multiple databases that use different filters is that if you turn on a filter, you may be limiting perfectly good results from databases that don't use those filters.

To conduct a completely comprehensive literature review, you should search each database independently, which will allow you to take full advantage of the limits set up for that database.

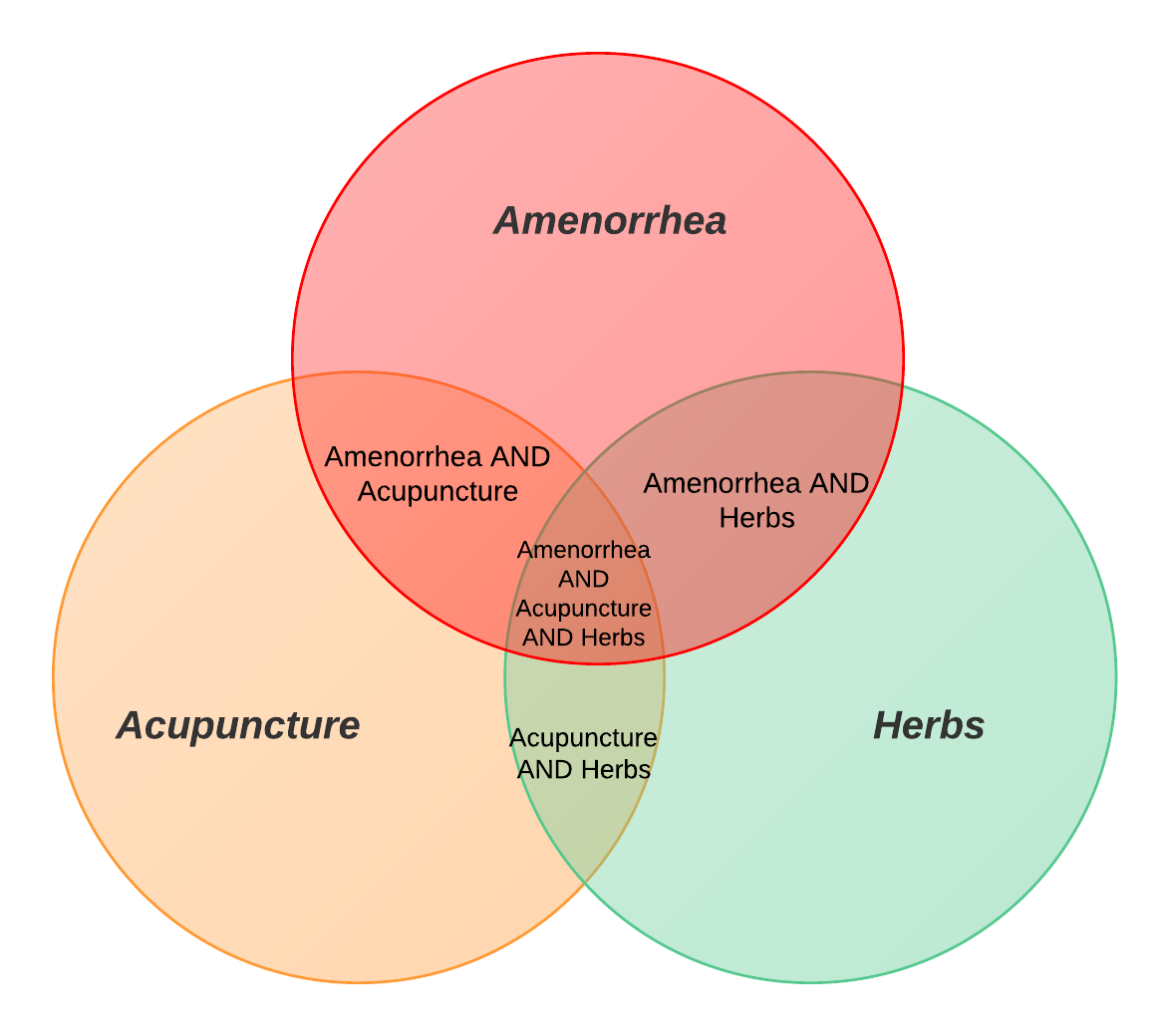

Boolean operators are how we modify searches. For example, let's say you are searching for acupuncture or herbal treatments for amenorrhea.

Use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) to combine or exclude search terms:

If you wanted to find information about acupuncture OR herbs in the treatment of amenorrhea, you would use parenthesis to set your search phrase. Look at this search phrase:

Boolean formulas read like a mathmatical formulas, from left to right. So this search phrase would retrieve Amenorrhea AND Acupuncture. OR it would just search Herbs. In order to remedy this, you should use parenthesis to define your search parameters:

You can use the asterisk symbol to create truncation and wildcards, which will allow you to account for variations in spelling.

Acupunctur* = acupuncture or acupuncturist

Find the Help section in the catalog / database you are searching to learn more.

When you find references in a bibliography, you are looking at older research -- stuff that was written that influenced the newer article or book. But using a Google Scholar function, you can flip this and search for newer research. If you've found a good article, you can try searching for it in Google Scholar. When you find the article, there will be a link that says, "Cited by ___," with the number of found citations. If you click on the link, you will see all the newer citations that have referenced this article.

Researchers and publishers often do not publish results from studies that show negative or null results. This is not just a problem of publishers refusing to publish reports, but is often a self-imposed censorship by researchers who do not wish to showcase their unsuccessful trials. The problem with this is that journal publications are how researchers communicate findings to one another. You won't know that a type of therapy is not successful if people don't publish those results.

Grey literature is important because it fills this evidence gap. By searching for information that is not published, you can find information that you wouldn't necessarily find in commercial publications due to publication bias.

You can read more about searching for Grey Literature by checking out UBC's Guide.

- What patient populations are most likely to be affected by colon cancer?

- What are the symptoms of bacteremia?

- What are some common treatments for low back pain?

Background questions can be answered by using secondary resources such as informational articles, reference books, or clinical databases, and authoritative answers can be found in a short amount of time.

- What are the causes of surgical wound infection following hip replacement?

- What factors influence parents' decisions regarding the refusal to immunize their children?

- Does the use of cell phones increase the incidence of brain cancer?

Due to the complexity of the question, foreground questions generally require the use of scientific studies to answer, and may take much more research and time to answer.

I=Intervention or Indicator;

C=Comparison or Control (optional);

O=Outcome

EXAMPLE:

In older adults (P) does Tai Chi (I) compared to other forms of exercise (C) reduce fall risk (O)?

There are a couple of other letters you can also add to this mnemonic to ask different types of questions (i.e., PICOTT)

Type of Study: What kind of study would best answer this question (i.e., RCT, Case Series, etc.)

EXAMPLE:

Does telemonitoring blood pressure (I) in African-Americans with hypertension (P) improve blood pressure control (O) within 6 months of initiation of the medication (T)?

So let’s look back at our earlier example of Tai Chi helping to reduce risk of falling.

I=The Intervention is Tai Chi. Tai Chi is spelled a number of ways -- Tai chi chüan, Tàijí quán. So you may want to include alternate spellings (“Tai chi” OR Taiji OR “Tai ji”)

C=The Comparison intervention is other forms of exercise. This is pretty vague, using the term “usual care” can also be useful. You could try both terms by using (exercise OR usual care).

O=Finally, the Outcome is reducing fall risk. The generic MESH term that covers risk of fall is Accidental Falls, but there is also a sub-term that is prevention & control*. So you could use Accidental Falls/prevention & control*

Your boolean search could look something like this:

(elderly OR geriatric OR aging OR aged) AND (“Tai chi” OR Taiji OR “Tai ji”) AND (exercise OR usual care) AND (Accidental Falls/prevention & control*)

PICO is focused around an intervention. If you are not including an intervention in your literature search, you may spend a lot of time combing through results just to discover what kinds of interventions are available, and then having to narrow down your results. This can be avoided and time can be saved by doing some background research first, understanding what types of interventions are available, and incorporating that into your search.

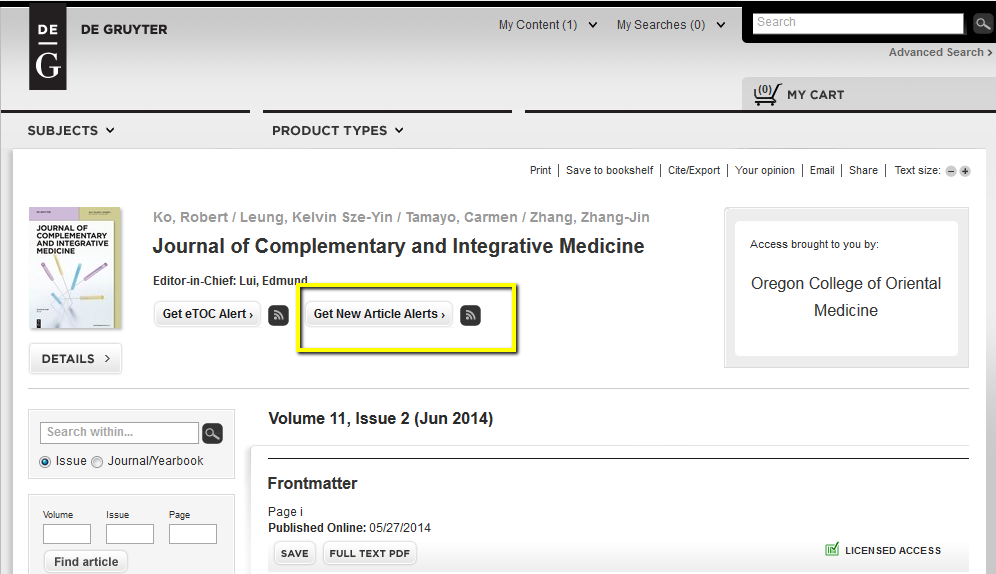

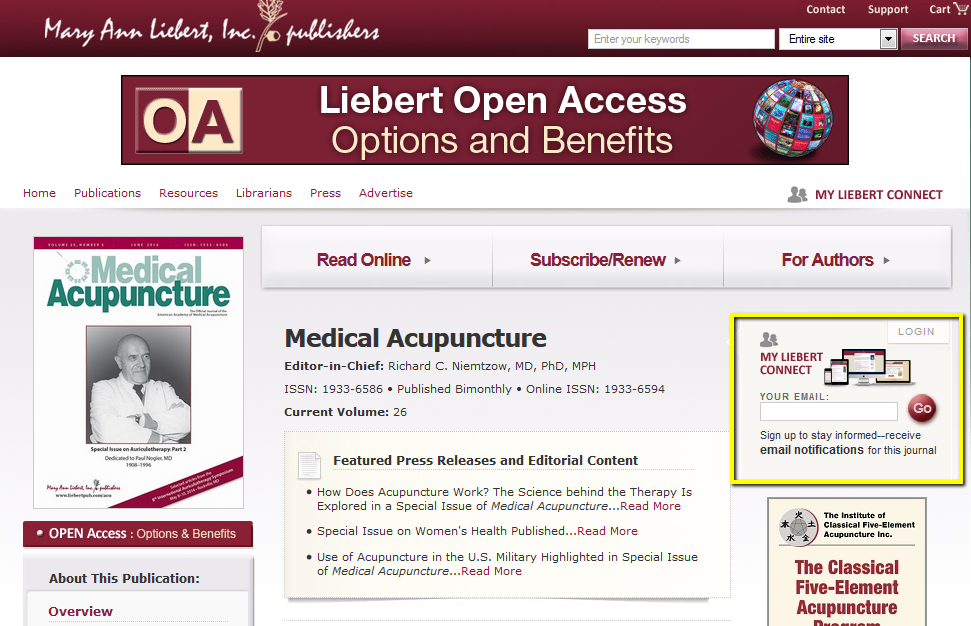

Push notifications are a way of getting alerted about new research. Say you are interested in keeping up to date about acupuncture / IVF research; rather than having to replicate your search each month or couple of months to see what is new, you can set up alerts that will automatically notify you when new material is published that meet your criteria. If you've ever used RSS feeds, you are already familiar with this concept: instead of visiting every website that you like, you can subscribe to the RSS feeds of your favorite sites, which will be aggregated into one place (your RSS reader) for your viewing pleasure. Here are a couple of ways you can use push notifications to stay up-to-date one newly published medical research.

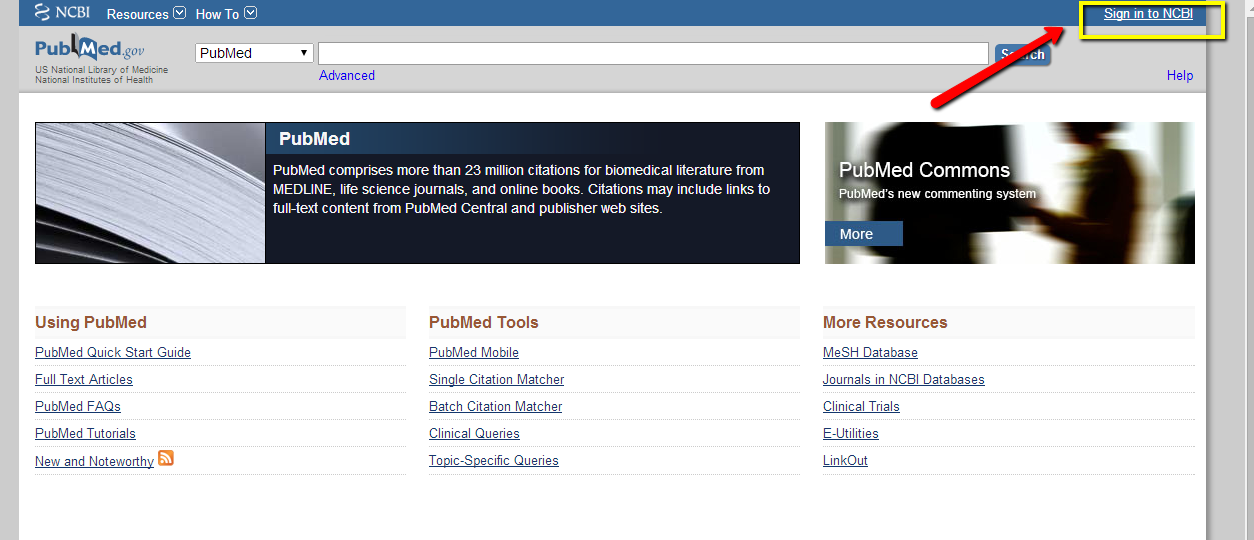

- Click on the Sign In button in PubMed.

- Register for an NCBI account, or log in using your Google account

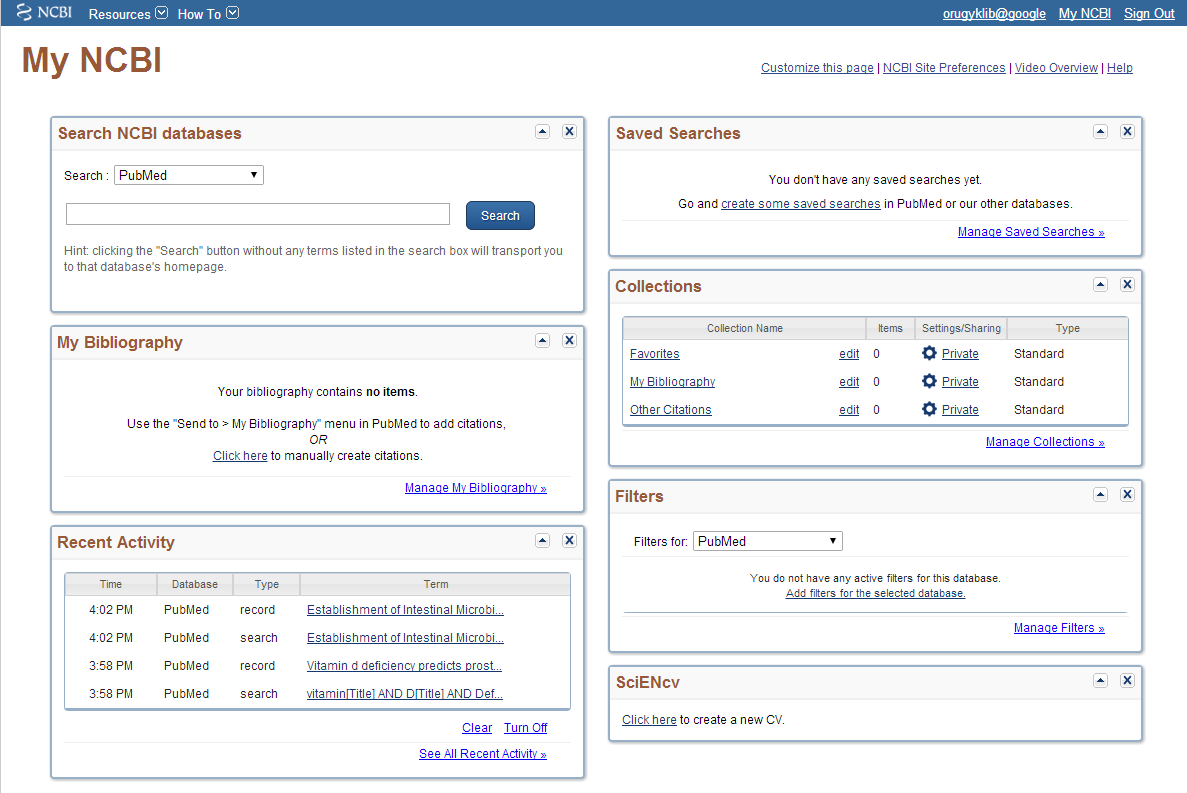

- Once you are registered and signed in to My NCBI, you see your dashboard. Here, you can search for articles in PubMed, create a bibliography or a collection, see recent searches, create active filters, and manage your saved searches.

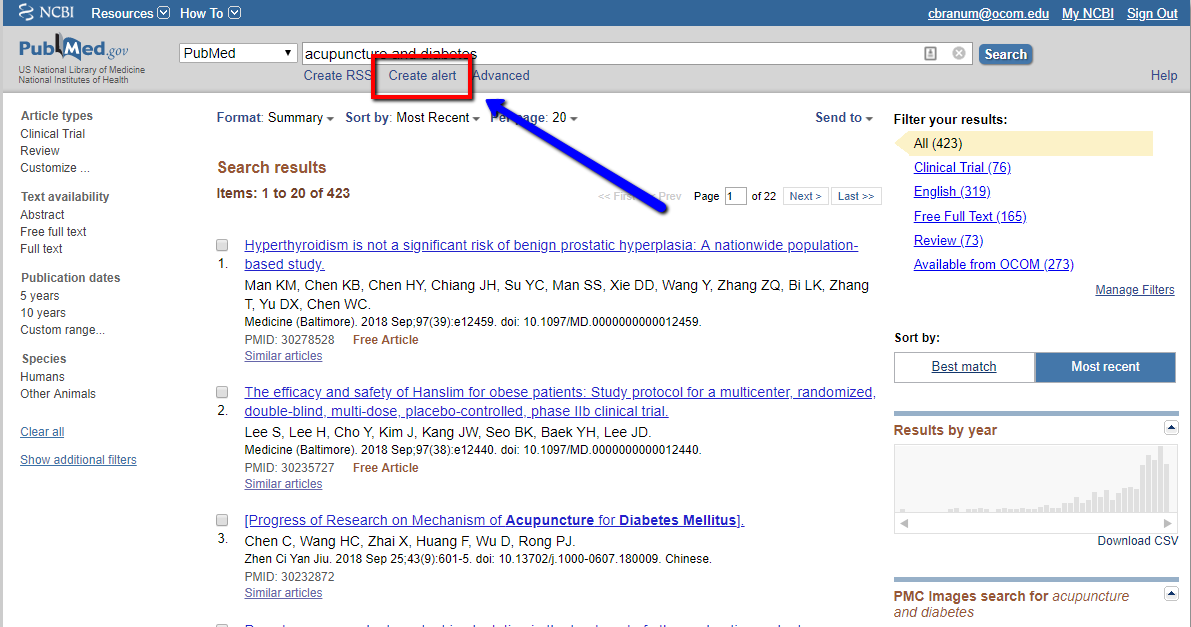

- In order to save a search, simply do a keyword search in PubMed, then click on the "Create alert" link.

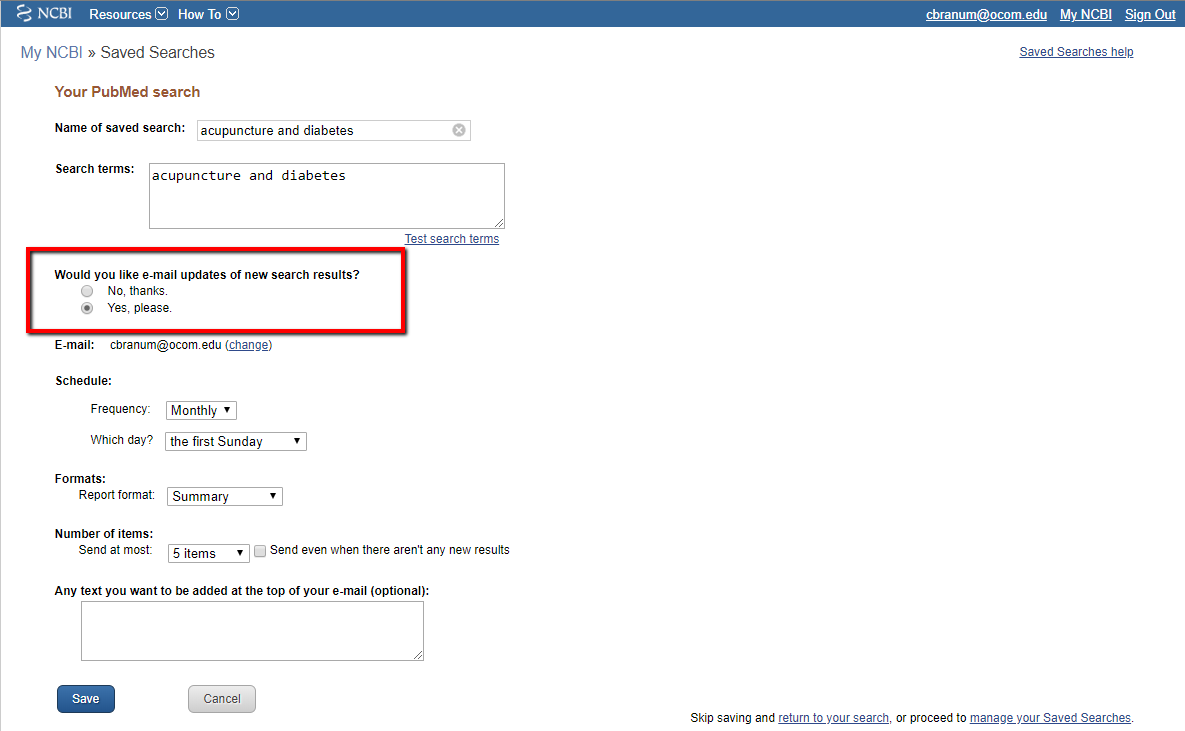

- Once your search has been saved, you can set it up so new articles that match your search will automatically be emailed to you. You can always edit your search and modify your keywords or filters if you are receiving too many or too few results.

- Sit back and wait for your articles to be delivered to your inbox!

You can also get notifications from specific journal publications about newly published articles that meet your search criteria. Most journals allow you to sign up for notifications by visiting the journal page on the publisher's site.