Origin and Purpose

Copyright is a type of protection given to an “original work of authorship” (Title 17, United States Code). The purpose of copyright is meant to promote the arts and sciences while still providing incentive for creators. The roots of copyright law started in Britain in 1710 with The Statute of Annae, which helped out authors who were being exploited by publishers, who were reprinting works and not giving a penny of the profits to the authors. Copyright law originally just encompassed printed works, but now copyright is involved in almost every aspect of life, from movies and music to databases and blogs. If you've every drawn a picture, written a poem, filmed yourself dancing, you are a copyright owner!

Requirements for Protection

It used to be that you had to file for copyright, but now, copyright is awarded to any original work in fixed medium, regardless of whether it is published or not. You no longer need to file for copyright; it is automatically granted once you create something in a tangible (or fixed) format. So while an idea is not copyrightable, a drawing or poem (even if scribbled on a napkin) is.

Copyright Protection and the Public Domain

United States copyright protection is currently set at the life of the author plus 70 years for works created since 1978, while works created before 1978 have different copyright duration rules.

For 2022: Works published prior to 1926 are now in the Public Domain, meaning that anyone is available to use, build on, or alter these works in any way without first obtaining copyright permission. In the U.S., work by people who died in 1951 are in the Public Domain.

When works pass out of copyright protection, they enter the Public Domain. This essentially means that they are owned by the public and that people can do whatever they want with them, including creating derivative works. This is how books like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies can exist without the new creator being sued. Every year that passes, new materials are supposed to enter the public domain, but this act froze it so that no new materials could enter the public domain until 2019. This is commonly referred to as The Mickey Mouse Protection Act because Mickey Mouse was just about due to enter the public domain when this Act was passed, keeping Disney’s rights to Mickey safe and secure.

A (very) Brief History

The Statute of Annae in 1710 gave authors rights for 14 years. Between 1790-1962, there wasn’t much of an increase in the length of copyright terms, but since 1976, modern the duration for U.S. Copyright Law has nearly doubled. The Sony Bono Copyright Extension Act of 1998 froze the Public Domain for 20 years.

Fair Use is an exception to copyright. Fair Use is often used in educational contexts "such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.” Copyright law is not supposed to stifle creativity, so this is where Fair Use comes into play. Fair Use makes exceptions for teachers using copyrighted materials in their classrooms, but could also include people remixing videos for satirical purposes, or the use of copyrighted materials to provide social commentary.

If you are confused as to whether the work you want to use falls under Fair Use, you can conduct a Fair Use analysis.There are four aspects to look at when conducting a Fair Use analysis:

- The Purpose, including whether it is for commercial or nonprofit educational use;

- The Nature of the work;

- The Amount used in relation to the whole;

- The Effect on the market or value of the work.

A Fair Use Analysis is not the law, but a guide. Each of these four aspects must be taken into account in conducting a Fair Use Analysis. If you do an analysis that comes out in your favor, it does not mean that you are exempt or that you are not infringing on copyright law – rather, it just means that there is a good chance that you might not be infringing. If you have doubts, you should always seek permission from the original copyright owner.

Stanford has an excellent Copyright & Fair Use site.

Columbia University's Fair Use Checklist is helpful for those looking to conduct a Fair Use Analysis.

Harvard has helpful informational graphics on Fair Use.

The Exclusive rights in copyright works are laid out in Title 17 U.S. Code § 106, sections 107-122.

All copyright owners automatically receive the following rights:

- Reproduce copies of their work

- Create derivative works

- Distribute copies or recordings of the work for sale, transfer, rent, lease, or lending

- The right to display or perform work publicly

Only the copyright holder has the power over these rights.

Certain types of works cannot by copyrighted, such as:

- Facts and ideas

- Raw data

- Works that are not set in a fixed or tangible form

- Titles and names

- Ideas, concepts, procedures, methods, discoveries, and facts

- Obvious works that do not have an author (for example, a 12-month Julian calendar)

- Works whose copyright has expired and is in the Public Domain

It is important to keep in mind that although facts (including recipes and formulas) cannot be copyrighted, the arrangement of these facts can.

Certain uncopyrightable works can be covered by other forms of law.

- Slogans and logos can be covered under Trademark Law

- Processes, methods, and systems can be covered under Patent Law

- Proprietary formulas and recipes can be covered under Trade Secret Law

If you have not secured permission to use a copyrighted work, then follow the following tips to follow Fair Use Guidelines:

- Only use a small piece of the item and only what is absolutely necessary.

- Only use it for personal and class-related purposes.

- Don't make a copy of the material available in any openly accessible fashion (including on the internet).

- Don't use it if you are in any way adversely affecting the commercial potential of the work.

- Make sure that you take your excerpt of the work from a legally-obtained version of the work.

Students may use copyrighted text, images, charts, diagrams and other material in school papers, as long as the material is cited properly. If you are planning on publishing your materials, even informally on the web, you will need to conduct fair use analyses for the use of copyrighted material and possibly pay a licensing fee or remove the material from your work.

More information on proper citations can be found in our AMA guide.

What You CAN Do

Students are allowed to make a single copy of a journal article, book chapter, chart, diagram, graph, drawing, cartoon, or picture from a book, periodical or newspaper for their own personal use, as long as it is not used for monetary gain.

What You CanNOT Do

Although students are allowed to make a single copy of a small portion of a work (an article, chapter, etc.), photocopying an entire book is not allowed.

The distribution of additional copies is also not allowed, including both print and digital formats. In addition, you should not make copyrighted works publicly available (such as posting them on a blog). Course Packs should not be further copied, as this may be a serious infringement of the College’s copyright licenses.

The duplication of A/V media such as audio lectures, music and videos are not covered by fair use; copying of these materials is strictly forbidden.

Royalties are paid for each copyrighted work used in a course packet and the cost is passed on to the students. Students will not be charged at a profit to the school.

Course Packs should not be further copied, as this may be a serious infringement of the College’s copyright licenses.

Any information on how to purchase a course packet should be included in your course syllabus. Please contact your instructor for instructions on ordering course packets.

If you would like to show a video, listen to a podcast, or otherwise display any copyrighted material during a live, in-person classroom presentation, you are free to do so! Just make sure you are not posting online or otherwise making the resource available outside of that class lecture.

To qualify for this exception, the work you are using fulfill the following criteria:

- Lawfully made and acquired.

- Only use a limited amount of the material.

- Limit the material used to current students enrolled in the course.

- Prevent further sharing of the material outside of the online classroom setting.

When making print or digital copies for classroom use, a copyright notice should be stamped on the first page of the material being copied (17 U.S.C. §401) and instructors must meet the tests of Brevity, Spontaneity and Cumulative Effect:

Brevity

- Poetry: (a) A complete poem if less than 250 words and if printed on not more than two pages or (b) from a longer poem, an excerpt of not more than 250 words.

- Prose: (a) Either a complete article, story, or essay of less than 2,500 words, or (b) an excerpt from any prose work of not more than 1,000 words or 10% of the work, whichever is less, but in any event a minimum of 500 words. (Each of the numerical limits stated in “i” and “ii” above may be expanded to permit the completion of an unfinished line of a poem or of an unfinished prose paragraph.)

- Illustration: One chart, graph, diagram, drawing, cartoon, or picture per book or per periodical issue.

- “Special” works: Certain works in poetry, prose, or in “poetic prose” which often combine language with illustrations and which are intended sometimes for children and at other times for a more general audience fall short of 2,500 words in their entirety. Paragraph “ii” above notwithstanding such “special works” may not be reproduced in their entirety; however, an excerpt comprising not more than two of the published pages of such special work and containing not more than 10% of the words found in the text thereof may be reproduced.

Spontaneity

- The copying is at the instance and inspiration of the individual teacher; and

- The inspiration and decision to use the work and the moment of its use for maximum teaching effectiveness are so close in time that it would be unreasonable to expect a timely reply to a request for permission.

Cumulative Effect

- The copying of the material is for only one course in the school in which the copies are made.

- Not more than one short poem, article, story, essay, or two excerpts may be copied from the same author, nor more than three from the same collective work or periodical volume during one class term.

- There shall not be more than nine instances of such multiple copying for one course during one class term. (The limitations stated in “ii” and “iii” above shall not apply to current news periodicals and newspapers and current news sections of other periodicals.)

BOOK CHAPTERS:

Instructors may post up to two scanned book chapters in Populi for use in their course without having to secure copyright permission, provided that the scanned material is equal to less than 10% of the entire book. Please remember to include the full citation and copyright information along with the scanned chapter(s). If you are using more than two chapter, more than 10% of the work, or if the book chapter is used repeatedly (i.e., the scanned chapter(s) were used in the course last year, and you want to use them again this year), copyright permission needs to be secured. Fill out the Course Reserves Request Form if the book chapter(s) you would like to use meet any of these criteria.

IF THE ARTICLE / BOOK CHAPTER IS AVAILABLE FROM OCOM'S COLLECTIONS:

You are welcome to use journal articles and eBooks from the Library's online collection without seeking permission. Our contracts allow for use in course reserves, so feel free to use anything from our collection! Just make sure you use the full proxied link (which begins with https://ezproxy.ocom.edu:2443/login?url=); more information about proxied links can be found below.

IF THE ARTICLE / BOOK CHAPTER IS NOT AVAILABLE FROM OCOM'S COLLECTIONS:

You can use the article or scanned book chapter for one academic term without seeking permission; use in subsequent terms will require us to secure copyright permission. If you used an article or scanned book chapter previously and would like to use it again for your class, please fill out a Course Reserves Request Form so we can make sure to secure copyright permissions.

If you do not already have a legally obtained copy of the article or book chapter, please submit an Interlibrary Loan Request Form to get a copy.

When adding video in Populi, if at all possible, link out to the material online! For example, if you find a YouTube video that you would like students to watch, do not download the video and upload it into Populi; rather, you can just embed the video into the lesson, or create a link to the video on YouTube.

https://ezproxy.ocom.edu:2443/login?url=

If you had to log in to view the article, your students will need to do the same! Any URL you post will have two parts: the proxy and the permalink. EXAMPLE:

For articles found directly from journal publisher websites, the permalink is just the regular URL from the web browser. So just copy the URL in your search bar, and add the proxy to the beginning of it.

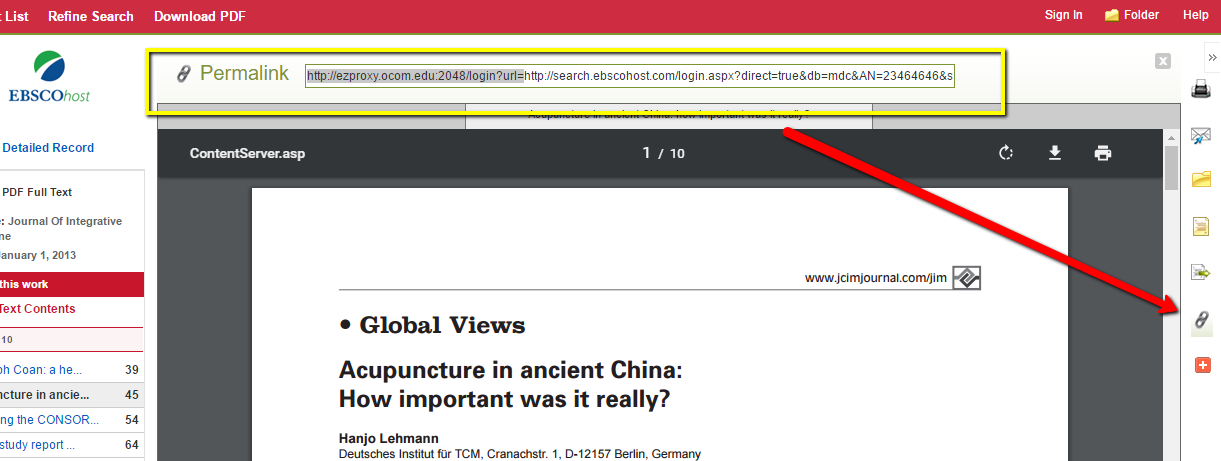

Articles found in databases (such as EBSCO host and Gale) often have a built-in option to create a proxied URL. Look for the permalink button, and make sure the proxy is at the beginning of the URL:

If you would like to post copyrighted information into Populi, here are some guidelines:

- Do not upload material that you do not own unless you have already received permission from the copyright owner to do so. If at all possible, link out to the material online. For example, if you find a YouTube video that you would like students to watch, do not download the video and upload it into Populi; rather, you can just embed the video into the lesson, or create a link to the video on YouTube.

- Feel free to link to websites and open access journal articles found freely available on the web.

- If you would like to post an article that is not freely available online or via the OCOM Library, you conduct a Fair Use Analysis. If you deem your use falls under Fair Use, then feel free to use the material. If you have concerns about its use, fill out a Course Reserve Request Form. A library staff member will legally obtain the article for you and send you a PDF or a link that you can then post into Populi.

Faculty members may request materials to be placed on reserve. Course reserves can be in electronic format (such as a PDF of a journal article that is posted in Populi), or the physical item may be placed on reserve in the library for 1 week checkout (for example, an entire book or a chart).

If you have already added the book to your list of required texts in Populi, there is no need to fill out this form – we will automatically place these items on reserve!

Please allow adequate time for reserve requests – we may need to request copyright permissions, which could take as long as a week to secure. To place a request, fill out this form.

If a student group or club would like to show a film, the sponsoring group will need to secure the proper licensing rights. Film showings that are organized by student groups or clubs are considered public performances, even if the film is educational or if the event is only available to OCOM students.

Many films (both documentaries and feature films) require a public performance license to be purchased. The sponsoring club is responsible for the funding of the performance license, and a license or permission must be secured even if the film is acquired from a personal collection, rental store, or library. For smaller, independent productions, students may contact the distributor directly to ask for permission. Proof of purchase of a required license must be presented to the Student Services Manager prior to advertising for the event.

If a student club requires assistance in locating information about the copyright holder, they may contact the Director of Library Services for assistance.

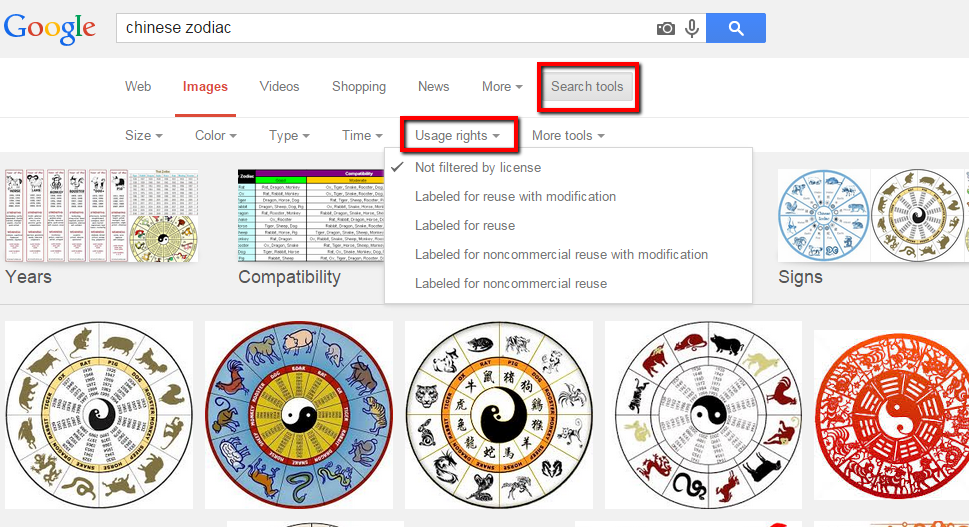

If you are not creating your own images (i.e. a graph, chart, or drawing) and are looking for images online, you need to carefully consider the copyright implications. You should never assume that images found online are free to use, many are in copyright. If you would like to use an image you found online in your research or teaching, you should do one of the following:

- Get permission from the image's copyright owner

- Buy you images from a reputable stock photo site

- Use an image that has been designated as being in the Public Domain or has a Creative Commons license

- Create your own images or take your own photos

Free and Legal Image Repositories

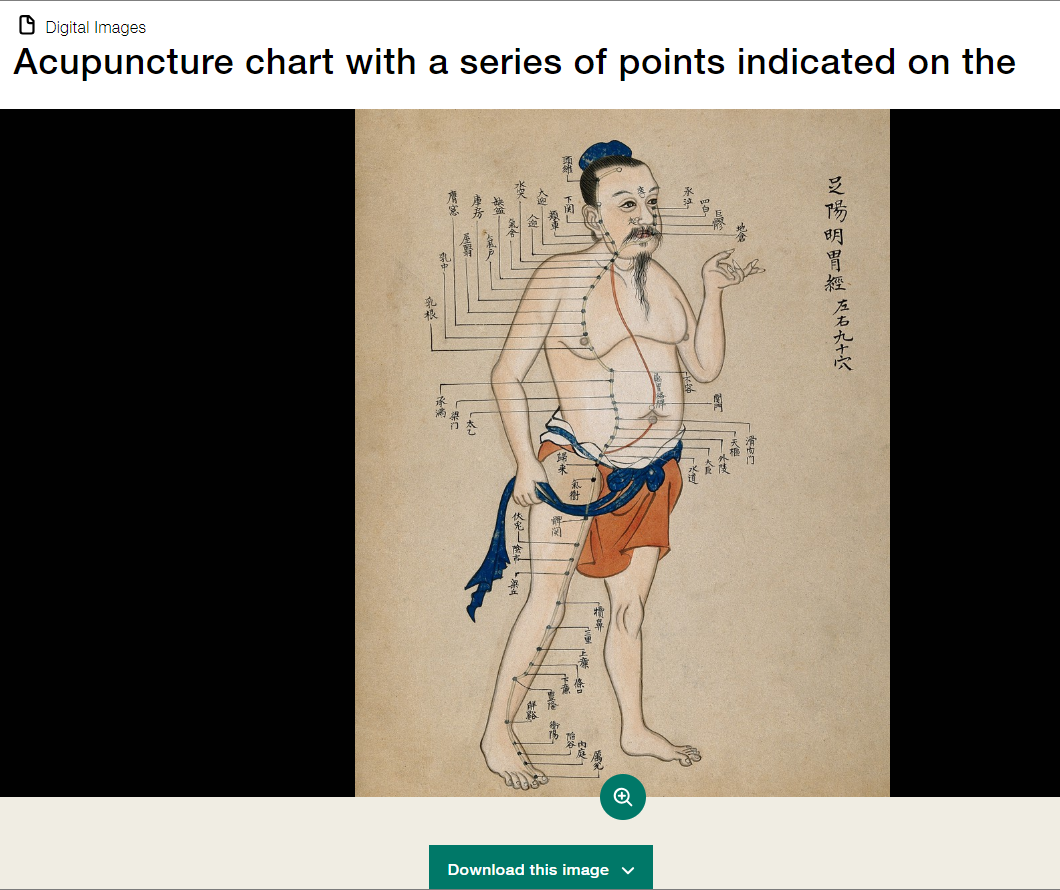

The following section details some online image repositories where you can find images that are free to use. Many have copyrighted content within as well, so always double check the rights information before using images in your work! Please note that for some of these sites you have to specify you are searching for Creative Commons and Public Domain Images.

Beware of image licensing sites, like Shutterstock or Adam, while there may be a Fair Use case for using images from these sites, the fact that they are available to license will weigh in favor of any use not being considered “fair”.

Some images in institutional collections, like the National Library of Medicine's History of Medicine archive, may have unclear licensing terms. You may see the license, "No Known Copyright Restrictions." In these cases, the institution believes the image to be in the public domain. For images from NLM's History of Medicine collection, they ask that if you use an image, to use the following credit: “Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, Maryland.”